- Home

- Art History

- Pop Art

Pop Art

Pop Art beginnings

In the 1950s, artists in both London and New York interpreted ideas about an overflow of mass-produced, commercialism and mass-entertainment. They called the apparent consumerism and commercialism – popular culture. Pop art produced colorful images based on advertising, the media and shopping. Pop artists featured movie stars, flags, packaging and food – things that everyone could relate to.

After the tragic early death of film star Marilyn Monroe in 1962, Warhol made more that 30 silkscreen portraits of her using a single reference, a black-and-white publicity photograph taken from her 1953 film Niagara. Warhol made a further set of prints in 1967.

After the tragic early death of film star Marilyn Monroe in 1962, Warhol made more that 30 silkscreen portraits of her using a single reference, a black-and-white publicity photograph taken from her 1953 film Niagara. Warhol made a further set of prints in 1967.Deliberately different from traditional fine art, Pop art subjects were brazen and accessible and technical skill was often disregarded. The art commented on post-WWII society, embracing materialism and blurring distinctions between commercial art and fine art. By employing production techniques used on advertising, such as silkscreen printing and sign writing, they made paintings that did away with a degree of artistic expression, instead creating a recognizable product for an eager market place.

The distinction between artists and ordinary people grew less marked. Pop art revealed the aesthetic potential of the ordinary and the all-too-familiar. Pop art also reflected the optimism that people craved after WWII, rapidly gaining widespread popularity. Like pop music, pop art’s emphasis was largely on a celebration of the new modern world and newly empowered generation, pursuing the American Dream.

Brillo Box - by Andy Warhol

Brillo Box - by Andy Warhol

Pop art made icons of the most ordinary consumer items, such as hamburgers, lawnmowers, lipstick tubes, a plate of spaghetti. Pop was easy to like. Its shiny colors, snappy designs – often blown up to heroic size – and mechanical quality gave it a glossy familiarity. Sometimes Pop artists produced work that could be interpreted as a critique of modern consumer society rather than an endorsement. Despite the ambition to break down distinctions between elites and mass culture, Pop artists remained predominantly producers of works that were exhibited in galleries and collected by the wealthy, the high value of which depended upon their uniqueness and authenticity.

Pop seeks a hard, impersonal objectivity, taking the commonplace out of context and makes us look at it anew, not simply use it. Ordinary objects become the focus of contemplation.

Pop artists had different agendas and developed along different trajectories. Several artist became Pop after having worked in advertising.

Andy Warhol

One artist who gained Pop fame after working in

advertising was Andy Warhol.

Warhol said, “Once you begin to see Pop, you can’t see America in the same way.” Warhol made a point about the loss of identity in industrial society.

In 1962 Andy Warhol produced a series of thirty-two silkscreen paintings depicting soup cans - one canvas for each variety of Campbell's soup available at the time.

- Warhol: “The reason I’m painting this way is that I want to be a machine.”

- Warhol brought art to the masses by making art out of daily life.

- Warhol also famously silk-screened the movie star, Marilyn Monroe.

Having been the most successful and highly paid commercial illustrator in New York, Warhol became a leading Pop artist, one who changed the status of art and attitudes towards it, including what materials and subjects were acceptable. Exploring commercialism and consumerism, his visual commentary of society's obsession with celebrity and the expansion of mass media was prophetic.

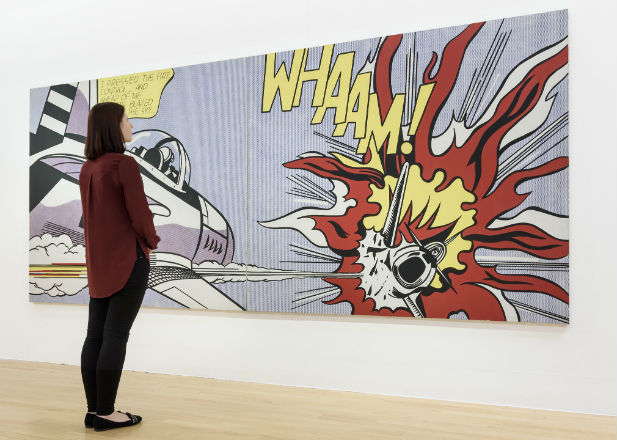

Roy Lichtenstein

Another Pop artist, Roy Lichtenstein, like Warhol, challenged the boundaries between materials and processes. They blended painting, printing, and photography.

Lichtenstein’s most famous work is Whaam! which used comic book imagery.

Lichtenstein pursued an educational path that led him to teaching while he continued to paint. His style evolved until he adopted Pop art imagery and became known for his works based on comic strips and advertising imagery, colored with his signature hand-painted dots (reproducing by hand that which would have appeared in printing processes).

Key Artists:

|

Pop artists, as they became known, produced colorful images based on ...

... things that everyone, rather than just a highbrow few, could relate to. |

Key Developments

Radically different from established art ...

- Pop art reflected the optimism that people craved after World War II and it gained widespread popularity.

- With its irreverence and focus on contemporary culture, Pop art shared some aspects of Dada, but was never angry.

- Like pop music, its emphasis was largely on a celebration of the new modern world and a newly empowered generation, but it had political aspects too.

By the end of the 1960s, Pop art’s vigor was fading, though many artists continued. Yet, Pop art was one of the first Postmodern art movements, and also the first serious attempt to face up to the problem of where the fine artist and his product – the unique, authored work of art – fit in the modern world.

- "Pop artists

acknowledged the artist’s loss of the monopoly of images, of

aesthetic creation and of Beauty." - Eco

- “One of the duties of art is to make you look at the world with pleasure. Pop art is the only movement in this century that has tried to do it.” - Philip Johnson, Pop art collector.

Eco, Umberto. History of Beauty. Rizzoli 2004. p. 377

Okay, so now I've put on some ads from Amazon - from which I may earn a few cents. (2025)